Rematriating Land Back Now

(a 10-minute read)

You may have heard the good word about the Wildcat Canyon Community School’s intention to rematriate land to Sogorea Te’ Land Trust (STLT), or maybe this is the first time you are hearing the word rematriation. Either way, as we near the end of our first school year as Wildcat Canyon Community School (WCCS), this blog post is an effort to share information across our school community about what it means to rematriate land, how our school came into such a privileged position to consider giving land back to a local Indigenous group, and what we might be able to expect as a community as we go through the process of rematriating the largest acreage of land back to Indigenous stewardship in the Bay Area.

Rematriation is a concept that Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and other Indigenous women-led organizations use to talk about the practice of restoring a people to their rightful place in sacred relationship with their ancestral land. The Sogorea Te’ Land Trust is an urban land trust founded in 2012 by Corrina Gould and Johnella La Rose with the goals of returning traditionally Chochenyo and Karkin lands in the San Francisco Bay Area to indigenous stewardship and cultivating more active, reciprocal relationships with the land.

The Future is Indigenous Art by @ines_ixierda

Corrina Gould and Johnella La Rose

Corrina Gould (a Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone leader) and Johnella LaRose (of Shoshone–Bannock and Carrizo heritage) met as mothers and activists many decades ago. To give some context to the Native experience in the Bay Area over our lifetime, between 1952 and 1973, the US federal government attempted to move Native Americans off reservations and into urban areas under the promises of financial assistance and job training, called the Indian Relocation Act. It wasn’t until 1978 that Indigenous people in the United States were even allowed to legally practice their spirituality; even efforts to save feathers, perform traditional dance in public, or have sweat lodges were illegal. By the time the American Indian Religious Freedom Act finally passed in 1978, there was already a resurgence of Indigenous people fighting for social justice in the Bay Area, and Ohlone people were engaged in efforts to reclaim their land and to revitalize their language and culture.

Campaign poster to stop development in Vallejo

In 1998, Corrina and Johnella co-founded an important Bay Area institution called Indian People Organizing for Change (IPOC). IPOC was invited by the Vallejo Inter-Tribal Council in 1999 to work together to save a village site at Glen Cove. Johnella informed me that for many tribes of the region and beyond, this village, whose original name was Sogorea Te’,was a major trading and political meeting place, along the Karkin strait. While the development at Sogorea Te’ was ultimately halted, the land was not turned over to the Ohlone people, as they are denied recognition as a Native American tribe by the federal government of the United States. Instead, the land was transferred to the nearest federally recognized tribe, the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation, which lacked any connection to the location or to the occupation, and consequently gave significant concessions to the land developers.

To prevent a similar situation from occurring again, the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust was founded in 2012 by Corrina Gould and Johnella LaRose as a way to collectively own title to the traditional lands of the Karkin and Chochenyo Ohlone people. The first plot of land for the Land Trust was donated by Planting Justice in 2017, a nonprofit organization dedicated to local food and economic justice located on 105th Avenue in East Oakland, co-founded by myself and Gavin Raders in 2009. Gavin and I had the opportunity to meet Johnella and Corrina in 2017; we were introduced by our colleague Diane Williams, who is Athabascan and brings decades of experience to the Planting Justice team. Others have also joined in these efforts by giving Shuumi and rematriating land and now several small plots in the East Bay have been returned to Indigenous stewardship through the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust.

Images pulled from STLT Facebook, March 10, 2022

Now that we’ve covered a brief history of how Sogorea Te’ Land Trust formed and what rematriation means, let’s turn back to understanding how Wildcat Canyon Community School came into the position of having all this land to give back. To tell that part of the story, it’s important to first understand the history of colonization on this land.

El Sobrante in Spanish means “the leftovers,” which may lead one to imagine how the Spanish Rancheros perceived this land that sits just over the hills of the East Bay. El Sobrante historical records show that an Ohlone village was located where the El Sobrante Library now stands, and the Ohlone people left a now-buried shell mound beside San Pablo Creek. Corrina Gould has done numerous presentations around the Bay Area and around the world speaking to the issues Ohlone people face on this land surrounding the Bay. This conversation Johnella LaRose had with Corrina Gould and a reporter in 2017 tells about their experiences organizing in the Bay Area throughout the past few decades, and if you have more time, we recommend listening to this longer-form presentation that Corrina Gould recorded recently at UC Berkeley, which includes a slide deck that Corrina put together with great information (note: Corrina’s introduction begins at 16:30 and her presentation starts at 18:00).

Many of us have some reference to the Missions in California, a series of 21 religious + military outposts founded by Catholic priests of the Franciscan order, established between 1769 and 1833 from South to North in what is now California. The missionaries systematically forced the Ohlone people living in this area to Mission Dolores in San Francisco, where they were separated from their families, and either killed or forced into a life of slavery, Christianity, and ranching. I don’t know about how the picture was painted through the education you received while growing up, but I was not taught history from this perspective in my public school here in California. In fact, we were taught to celebrate the CA Mission system. Once I learned about Ohlone people’s history, I became determined to not sustain my children with lies meant to perpetuate white supremacy. Throughout Oakland today, many third and fourth graders’ in the public school system have the opportunity to hear from Corrina Gould, her daughters Deja and Cheyenne, and other Ohlone educators such as Ruth Orta, Kanyon CoyoteWoman, Vincent Medina, and others who teach about Ohlone people’s history.

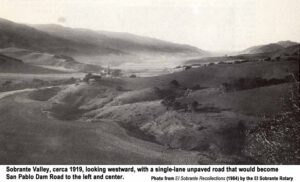

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1834, enslaved Ohlone people were set free from the mission system. However, their villages and hunting grounds were then all “owned” by Spanish colonizers who were given Spanish land grants. A large parcel of land east of the shoreline that would become Richmond and vicinity were all part of Rancho de San Pablo. Further east, all the way to and including the hills that fed the creeks in Sobrante Valley and the adjacent areas, was Rancho El Sobrante. When the Ohlone attempted to return to their former villages, they were chased off their ancestral land and sometimes killed by so-called legal landowners for “trespassing.” Rancho El Sobrante was eventually sold off into smaller ranches. In the early 1900s, Sobrante Valley consisted only of these ranches and a single-lane dirt road that ran down the valley floor, alongside San Pablo Creek. Gradually, these ranches were further divided into even smaller farms and ranches, some of which were further subdivided into large lots, which were sold for building houses. As this process progressed, rural El Sobrante became a semirural community that remains unincorporated in Contra Costa County.

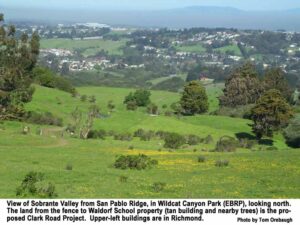

Since the 1970s, semirural El Sobrante became increasingly urbanized by developers interested in building housing projects on ranches and farms, but the community began to fight back against this unchecked urbanization by organizing spunky grassroots groups, earning El Sobrante the reputation of being a difficult place for large developers to get their subdivisions approved. Several housing and commercial projects were blocked, and those that have been built had to be scaled back before being approved. Residents from El Sobrante, Richmond, and our surrounding area have been diligently working to Save the Richmond Hills. The Richmond Hills Initiative (RHI) protects 430 contiguous acres which includes the 80 acres donated to our school. RHI has been guided from its inception by a core group of neighbors – Jim Hogan, Sarah Willner, Deborah Schmidt, Joanne Spalding, Cary Groner, Janet Kutulas, Peter Simcich, and later Robin Bedell-Waite. It’s also important to acknowledge the past efforts of Eleanor Lloynd, and the many unsung heroes of the past who fought to protect the hills, fending off development after development.

The area to be protected by the RHI is shown in blue on the map

In 2015, the Save the Richmond Hills group enlisted the support of Dick Schneider from the Sierra Club, and from there they decided their best path forward was to attempt a blanket protection of a large area, similar to the Hercules Franklin Canyon Measure M. With the assistance of Professor Robert Girard of Stanford University, they worked out the details of the Richmond Hills Initiative, and then met with City Council members and Richmond staff to iron out certain aspects of the proposal. The entire process of writing the Initiative took them almost a year. But they still needed to gather enough signatures of registered Richmond voters to qualify the Initiative for the ballot, which would enable it to be adopted by the City Council or placed on the ballot for voter approval. Throughout the Summer of 2016 they had a massive signature-gathering drive. They originally hoped to get all the signatures at stationary points – markets, festivals and the like – but soon realized they would need to canvas door-to-door, a much slower and more laborious process. The signature-gathering drive went on for six long months. After intense vetting of the signatures for validity, they submitted the Initiative for Qualification for Ballot on December 6, 2016, and after the successful validation of the signatures, the City Council adopted the RHI in a unanimous vote on January 24, 2017.

After the RHI went into effect in early 2017, four of the development speculators who own parcels in the RHI area filed suit against Richmond in an attempt to overturn the initiative. In order to hire legal assistance to support the City’s case, the group began a fundraising drive which, thanks to some of our school community’s generous help, was successful. The case was heard on January 3, 2018. The judge’s ruling in early May of the same year upheld every protective aspect of the Initiative, but found that they had created an inconsistency between the RHI and Richmond’s Land Use maps, a small technical flaw. Rather than sending the RHI back to the City to be fixed (as the group believed the court was required by law to do), the judge invalidated the Initiative entirely. So the group then had to file an appeal of the trial court decision, raise more money, hire new legal counsel, and on October 26, 2019, they emerged victorious at the Court of Appeal with a ruling directing the City to cure the inconsistency between the Initiative and the city’s General Plan. The group worked with the City to create that cure, which was approved unanimously by the City Council on April 6, and on April 29, 2021, the writ was returned to the court and the RHI’s status was no longer in any doubt.

But the RHI isn’t a done deal yet…Another major investor/landowner in the Richmond hills, who still retains hope of large-scale tract development on their land, launched another legal challenge in October 2021. It’s being presented in two phases. The first phase has already been through the courts and thankfully was quickly and summarily dismissed. The next phase is coming up later this year after several postponements, and so the Save the Richmond Hills group is still poised to raise more funds to again pay their lawyer to assist the City of Richmond in the defense of the Initiative. Many of them are musicians, and held a previous fundraiser hosted by the former East Bay Waldorf School which successfully raised funds towards this endeavor (we should consider organizing a similar event).

We believe the developer that owned the 80 acres adjacent to our school, Gray1 Forest Green, a San Diego based company, saw the writing on the wall and didn’t want to pay taxes on the property anymore, nor be pressured into lawsuits. To our community’s benefit, they decided to donate the legal title of the land to East Bay Waldorf School in May 2019. When I first heard this news, my mind turned toward our local community’s history of attempted genocide, enslavement, resistance and rematriation. At the time, my older child Azadeh was in public school. She had attended East Bay Waldorf School for preschool, but when it came time to pay for kindergarten, our family decided we couldn’t afford to keep her enrolled. We kept in touch with Teacher Emily, who through her own accord had made sure to invite Corrina and Johnella to come visit the school and meet the EBWS school board.

Johnella, Haleh and Corrina at the Planting Justice office in 2017

Gavin Azadeh and Ayla at the Intertribal Friendship House in 2018

Covid-19 changed everything as we know, and in that time Wildcat Canyon Community School blossomed through each of our connections to this land and special school. That’s quite another story for another blog post…. Gavin and I decided to join the many other volunteer Circle of Trustee members to help with re-starting the school back in December 2020. In August 2021, Gavin and I submitted a proposal for the WCCS Circle of Trustees to consider transferring the legal title of 79 acres to Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, and for WCCS to create a cooperative use agreement with STLT to give WCCS access with the ability to cultivate a more active and reciprocal relationship with the land.

From my vantage point, as the daughter of an immigrant from Iran, who was born in California in a mixed-race household and educated by the California public school system, I am firmly and deeply committed to the process of rematriating land back to Indigenous people. Rematriated land provides sacred space for Indigenous people to practice traditional ceremonies and to grow native, edible, and medicinal plants. For example, at Lisjan, which is a traditional village site in deep East Oakland where Planting Justice partners with STLT, they’ve built the first ceremonial arbor in the Bay Area in over 250 years since the CA missionization period. STLT (and the school) would both benefit from mutual land stewardship: gardens, farming, outdoor classrooms, fire management. STLT’s existing gardens operate on a free food/gift economy for families in need. They tend the land through a holistic approach guided by traditional knowledge and practices. STLT brings with them an energized community of volunteers and staff. Land rematriation is an act of justice. It does not mean we lose access; and it requires that we shift from a colonial way of thinking, every day in so many ways.

During the Fall season of 2021, the Circle of Trustees had the opportunity to convene twice with the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust community. During our first visit together, the WCCS community presented handmade gifts and other items to the STLT crew, and we walked up the road that cuts through the middle of the 79 acres up and around to a special clearing, with kids in tow and small groups conversing and moving at different paces. Our second visit bringing together the WCCS and STLT communities focused around Chad Estep and his family, who lease and manage a portion of the 79 acres for horses, llama, chickens and more. Both groups reported back positively about the other with appreciation for the opportunity to collaborate and continue a formal partnership on the land.

On Monday May 2nd, 2022, the Wildcat Canyon Community School’s Circle of Trustees unanimously consented to sending a Letter of Intent to Sogorea Te’ Land Trust to begin the legal process of rematriating 79 acres of land back. The WCCS Circle of Trustees is made up of myself, Haleh Zandi, and Gavin Raders, Meaghen Liebe, Jubilee Daniels, Vika Sirova, Melanie Hatch, Alvin Lopez, Gwen Gruesen, Haley Pollock, John Silliphant, Stacey Pelinka and Jessa Moreno.

Saturday June 4th, 2022 is the next planned gathering for our school community to break bread and deepen connections with the Sogorea Te’ community, and we invite you to join us in the school garden from 10am-12pm that day. The Circle of Belonging will be in touch soon with further details.

I’m sure each of us have a unique story to share about how special the land around the school is, and I can’t help but imagine how Corrina feels to walk around our beautiful campus. Rematriating land is not the only thing our school can do to shift our community towards the arc of justice. The Ohlone people face many challenges in their homeland, which include revitalizing their language, protecting sacred sites such as the West Berkeley shellmound, feeding communities throughout the area affordable nutritious food, having safe and dignified housing for all community members, resisting state-sanctioned violence and family separation, and other pressing issues.

Images pulled from Sogorea Te’ social media

There are many ways our school community can step up to support at this time. I encourage you to consider paying the Shuumi Land Tax, a voluntary, annually recurring contribution that non-Indigenous people living on traditional Ohlone territory make to support the critical work of the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust. Please follow the work of Sogorea Te’ online, share their content, and take action when called upon. Teachers Chimay and Marcus suggested to the Circle of Belonging that we all help each other to learn Ohlone names for the plants we enjoy and the special life that we share this land with. There are many ways that our community can bring the rematriation process into our school’s curriculum.

hen you’re going out to eat locally, consider visiting Wahpepah’s Kitchen at the Fruitvale BART station or Cafe Ohlone on UC Berkeley’s campus. Let’s invite more Indigenous speakers to engage with our school community, such as our experience with Roman Vizcarra. I appreciated the opportunity to bring attention to Indigenous struggles and workers’ rights during our Springtime Jubilee. What else should we be doing? The time is now!

With respect,

Haleh Zandi, on behalf of the Circle of Belonging at Wildcat Canyon Community School

Please contact diversity@wildcatcanyon.org with any comments or inquiries

Posters made by Wildcat Canyon Community School students during the 2022 Springtime Jubilee

Photo credit Sarita Doe

Please contact diversity@wildcatcanyon.org with any comments or inquiries about our June 4th gathering. Comments or questions about the land rematriation process in general should be directed to trustees@wildcatcanyon.org.